In an era where technology and art increasingly intertwine, a

groundbreaking installation titled

"Living Type River: Hydraulically Driven Poetry

Recomposition"

has emerged as a mesmerizing fusion of engineering and literary

expression. Conceived by interdisciplinary artist collective

AquaText, the piece transforms language into a

dynamic, ever-changing entity—powered entirely by water.

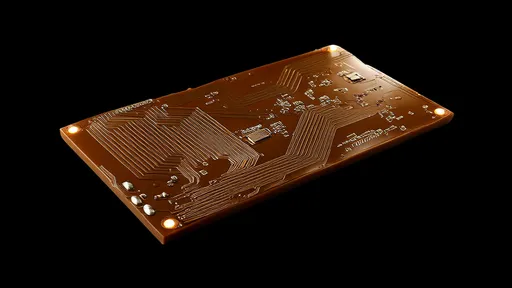

Housed within a repurposed 19th-century pump station along the Rhine,

the installation comprises 3,600 bronze type characters suspended on

thin cables above a circular water channel. As visitors approach,

hidden turbines spring to life, generating currents that make the

letters sway and collide. What begins as random movement gradually

coalesces into readable fragments—lines from Hölderlin, Dickinson,

Neruda, and Bashō emerging like messages from the deep before

dissolving back into the aquatic chaos.

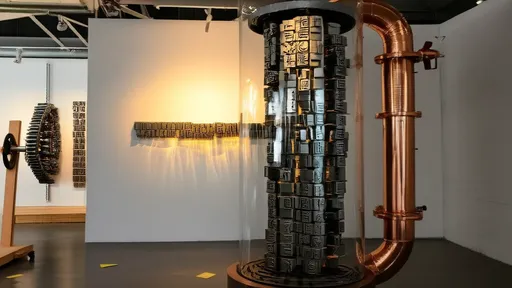

The true marvel lies in the hydraulic "logic engine" powering the

system. Designed by Swiss kinetic sculptor

Lise Moreau, this labyrinth of glass pipes and copper

valves uses water pressure to "remember" poetic sequences. When

certain letter combinations align correctly, sensors trigger submerged

pumps to reinforce that particular flow pattern—a literal

manifestation of linguistic currents finding their course.

<

Unlike digital poetry generators, the

Living Type River embraces physical constraints. Rust

forms on neglected letters, heavier characters move slower, and

seasonal humidity alters the system's rhythm. During a recent autumn

storm, the installation spontaneously recomposed Rilke’s "Autumn Day"

as wind-driven rain disrupted the water patterns—an unplanned moment

that left viewers breathless.

Critics have noted how the work subverts traditional notions of

authorship.

"It’s not human, not machine, but something elemental—the river

itself becomes co-writer,"

observed Berlin Biennale curator Dominik Wessely. Indeed, visitors

frequently report pareidolia, seeing personal meanings in the

ever-shifting texts. A Japanese tourist swore the river spelled her

deceased mother’s name; a hydrology professor analyzed the patterns as

actual watershed data.

The project’s environmental statement resonates deeply. All water

circulates through the original building’s filtration system, while

the type was cast from melted-down fishing nets. At night,

bioluminescent algae cultivated in the channels make the letters glow

blue—a haunting effect that has drawn comparisons to medieval

manuscript illuminations.

As word spreads, pilgrimages by poets and engineers alike have begun.

Some come to witness what Borges might have called "the Water Library

of Babel"; others simply to feel the mist on their faces as language

materializes and vanishes like morning fog. The installation’s final

irony? Its most persistent poetic fragment—appearing 17 times during

testing—proves to be from Coleridge’s "Kubla Khan":

"Where Alph, the sacred river, ran / Through caverns measureless to

man..."

Now extended through 2025 due to popular demand,

Living Type River challenges us to reconsider poetry

not as fixed artifact, but as something alive—flowing, eroding, and

carving new channels through the landscape of meaning. Its creators

laugh when asked about preservation.

"How do you bottle a river?" Moreau shrugs.

"You don’t. You kneel at its banks and drink while you

can."