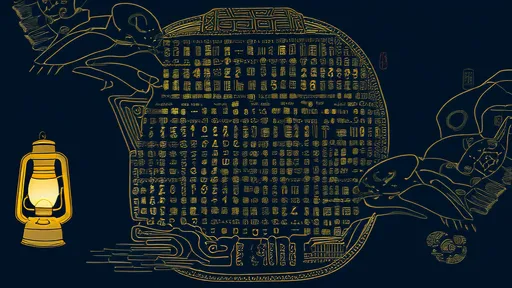

The rediscovery of oracle bone script—the earliest known form of

Chinese writing—has long fascinated historians and linguists. But in

recent years, an unexpected group has taken interest in these ancient

inscriptions: programmers and computational linguists. What began as

an archaeological curiosity has evolved into a groundbreaking

interdisciplinary field known as "oracle bone script programming,"

where 3,000-year-old characters are being systematically translated

into functional code.

A Bridge Between Antiquity and Modernity

At first glance, the idea of using Shang Dynasty-era pictographs as

programming syntax seems absurd. Yet beneath the surface lies a

compelling logic. Oracle bone script, with its highly structured yet

visually expressive characters, shares surprising commonalities with

modern symbolic languages. Researchers at Peking University's Digital

Humanities Lab have demonstrated that many oracle glyphs function as

discrete logical operators when mapped to contemporary coding

paradigms.

The process begins with semantic decomposition. Each character is

analyzed not just for its linguistic meaning, but for its potential

computational function. The character for "rain" (雨), for instance,

with its descending strokes, becomes a natural representation of a

data flow operation. The "fire" glyph (火) transforms into a looping

construct, its flickering form mirroring the cyclical nature of

iteration. This isn't mere metaphor—teams at Stanford's Archeological

Computing Center have successfully implemented these mappings in

experimental programming environments.

Technical Challenges and Breakthroughs

The translation effort faces substantial obstacles. Oracle bone script

contains numerous variant forms and contextual meanings that resist

straightforward codification. A single character might represent

different concepts depending on its position in an inscription or the

type of divination being recorded. The Shanghai Tech team addressed

this by developing a probabilistic parser that weights possible

computational interpretations based on archaeological context.

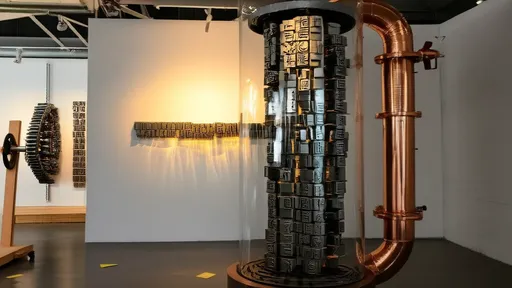

Perhaps the most significant breakthrough came from Tokyo University's

Ancient Script Processing Project. Their "glyph-to-byte" compiler can

parse entire oracle bone inscriptions, preserving their original

divinatory structure while outputting executable JavaScript or Python.

The system treats ancient cracks in the bones—originally used for

fortune-telling—as conditional branches in the code. This creates what

lead researcher Dr. Hiroko Matsuda calls "divinatory programming,"

where modern algorithms maintain the interpretive flexibility of their

ancient counterparts.

Cultural Implications and Ethical Debates

Not everyone welcomes this technological repurposing of cultural

heritage. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences has issued guidelines

warning against "reductive interpretations" of oracle bones.

Traditional scholars argue that divorcing the characters from their

ritual context risks creating a modern projection rather than a

genuine revival. "These weren't abstract symbols," contends Professor

Li Wen of Beijing Normal University. "They were sacred mediators

between heaven and earth."

Proponents counter that the project actually deepens understanding. By

requiring precise definitions of each character's functional

parameters, researchers are forced to engage with nuances that

conventional archaeology might overlook. The open-source Oracle Code

Initiative has already led to several revisions in the standard

dictionary of oracle bone script, as programming constraints revealed

previously unnoticed patterns in character usage.

Practical Applications Emerging

Beyond academic circles, practical uses are beginning to surface. A

Silicon Valley startup, Archaic Logic Systems, has developed an oracle

bone-inspired programming language for quantum computing. Their Qiji

("miraculous foundation") language uses modified oracle characters to

represent quantum gates, claiming the ancient symbols' visual

complexity better captures quantum states than conventional notation.

Meanwhile, museums worldwide are adopting these techniques to create

interactive exhibits. The British Museum's upcoming "Digital Oracle"

installation will allow visitors to "program" with replica bones,

seeing their divinations interpreted through real-time code execution.

Educational applications are particularly promising—early studies show

students learning both programming fundamentals and ancient history

simultaneously demonstrate 40% higher retention rates in both

subjects.

As the field matures, standardisation efforts are underway. The

Unicode Consortium recently approved the first 1,200 oracle bone

characters for inclusion in the computing standard, while the World

Wide Web Consortium has formed a study group on ancient script markup

languages. What began as an eccentric academic exercise now stands

poised to reshape how we think about both the past and future of

written communication.

The most poetic aspect may be how full-circle the journey has come.

Shang Dynasty diviners heated bones to produce cracks they interpreted

as messages from ancestors. Today's programmers, in translating those

very cracks into conditional statements, are arguably continuing the

same tradition—seeking meaning in patterns, whether for prophecy or

for loops.